What’s Holding Back the Adoption of Hosted Payloads?

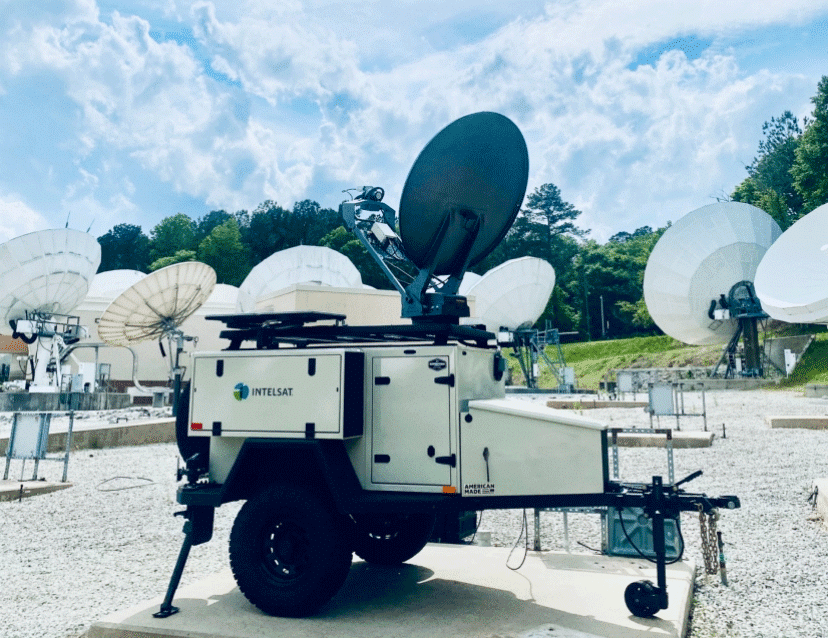

In such a climate, hosted payloads would seem to be an ideal solution. Commercially hosted payload refers to a payload integrated with a commercial satellite but operated independently from the main spacecraft. Discussions with the DoD around hosted payloads have been ongoing for years. Four years ago the Australian Defense Force (ADF) availed itself of the hosted approach and the MDA has recently announced an experimental network of commercially hosted sensors on LEO satellites which could turn into an operational system at some point.

However, with many space programs under review for next generational architectures and the existence of the Hosted Payload Solutions (HoPs) contract, the time is now for the DoD to make hosted payloads a resilient part of each new architecture.

Hosted payloads offer compelling advantages:

- Faster access to space. Roughly 40 commercial launches each year provide numerous opportunities and access to multiple orbit locations. When hosted payloads are designed in a modular fashion, they can be paired with commercial satellites for more rapid deployment into orbit.

- Greatly reduced cost. Placing a hosted payload on a commercial satellite costs a fraction of the amount of building, launching and operating an entire satellite because the expense of integration, launch, and operations are shared with the host satellite.

- Greater resiliency through disaggregation. Hosted payloads enable more resilient space architecture solutions. Rather than launching a few satellites with multiple capabilities that could be a lucrative target for adversaries, hosted payloads enable distribution of assets over many platforms and locations.

- Operational options. Hosted payloads can use existing satellite operations facilities with shared command and control of the hosted payload through the host satellite, or a completely dedicated and separate system operated by the hosted payload owner.

So why hasn’t an approach that is so objectively superior changed the status quo? Based on years of discussion within the industry and with government, I think it comes down to five major areas:

- Not Part of the Architecture. Currently commercially hosted payloads are not part of the architecture for any of the space-based mission area’s primary programs. These were free flyer programs when authorized and the options considered for augmentation included primarily buying more of the same. We call this the “easy button” and it has been pushed a few times already at the great expense of the American taxpayer. The problem with buying more of the same, is that the same is typically 10+ year old technology and extremely expensive. That legacy technology is not resilient or aligned to today’s threat environment.

- Lack of integration into CONOPs. This objection is a red herring, since the argument could be made about ANY new space program. Few of the current individual mission platforms are integrated. In fact, that’s the reason General Hyten is pushing to integrate current military constellations with a new Enterprise Ground.

- Need for launch flexibility. The current launch environment in the U.S. is fragile at best, and so opening up the options to include hosted payloads on commercial launches resolves tight manifests and increases rapid access to space. There is a mistaken impression that a hosted payload for the DoD would have to utilize a launch vehicle manufactured in the United States. This is inaccurate, and per National Space Transportation Policy language, hosted payloads on commercial satellites can utilize foreign launch vehicles with no waiver required.

- Primary mission timing issues. The acquisition process moves quickly in commercial, and often the slower government planning, programming, and budgeting process can create timing issues. The best way to address this is make the hosted payload part of the larger bus order to the manufacturer. This allows one company to manage the schedule, providing an incentive to honor deadlines and avoid program delays.

- Change threatens a major program of record. Pursuing innovation with the hosted payload approach often bypasses major integrators of free-flyer programs, and marries up the sensor or payload provider directly with the commercial operator. Indeed, a hosted payload could be seen as a line item expense within the primary program, so there is often little support from the prime contractor. In addition, DoD program office’s (PEO) hands are tied because the hosted payload is not part of the overall architecture or program. This is a cultural barrier that could be solved by making hosted payloads part of the options on a prime contract and incentivizing PEOs to look for cost-effective solutions that meet the mission needs throughout the life cycle.

The perceived hurdles to implementing hosted payloads are primarily cultural in nature, not technical. Yes, change is difficult, but the delay has been long enough. The objective benefits of hosted payloads are overwhelming, and new space realities demand new approaches.

As Abraham Lincoln famously said, “the dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate for the stormy present.” Together we need to start building the next generation of space architecture, and hosted payloads have a big role to play.