Sears: Commercial Wants to Help With Space SSA

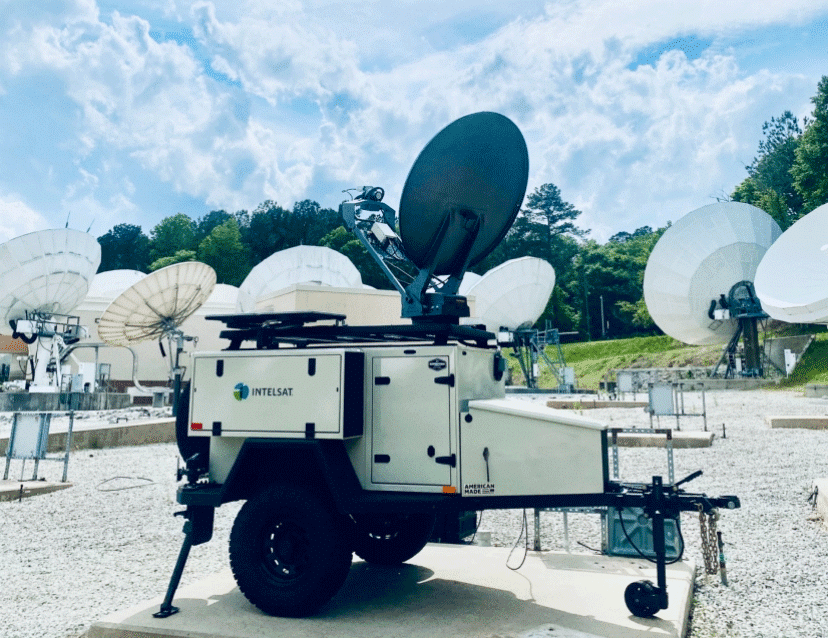

Greater commercial cooperation and data sharing services would help ease the burden on the Air Force for monitoring and reporting on the location of thousands of objects in space that can cause collisions and interference, Intelsat General Corporation President Kay Sears told a government forum recently.

“The commercial industry has to organize itself and expand what it can do on its own,” Sears said during a panel discussion at the Federal Aviation Administration’s Commercial Space Transportation conference in Washington on Feb. 2. “I also think we have to develop a set of best practices for space traffic management (STM) for all operators to adhere to.”

Much of the panel’s conversation centered around likely Congressional action to transfer monitoring of space situational awareness (SSA) and control of STM from the Air Force Joint Space Operations Center (JSpOC) to the FAA. The JSpOC has provided conjunction data to commercial operators since 2009, when a defunct Russian satellite and an operating Iridium satellite crossed paths and collided, creating more than 1,000 chunks of space debris.

However, the JSpOC was not created to provide this kind of service to commercial companies. Sears said that while the Center has done a great job, particularly by its recent inclusion of the Commercial Integration Cell, it is under-resourced to continue in a role that will only expand in an increasingly congested space domain, and it does not fit in with its core war fighting mission.

The global commercial satellite industry is ready to do its part. It launched the Space Data Association in 2010, with Intelsat as a founding partner, to lift some of the burden off the JSpOC and improve the data provided. Sears said that with even greater collaboration among commercial and civil space operators and with more transparent data exchange, the community can develop a product and process that will enhance the current situation in many ways, and will allow the JSpOC to focus on what it needs to do.

“If we really want to make progress, I believe personally … that we have to separate civil and commercial satellites from military and national security assets,” she said. “I think when you do that, you can design an acceptable framework for international cooperation.”

The burden of incorporating the military’s “unique needs, especially from a national security perspective, will slow down the process and may not produce the progressive results we need in the time we need them.”

Citing advancing use of space by companies interested in areas that do not yet exist, such as satellite services and mining, the panel also addressed an overhaul of U.S. commercial space regulation in response to the Space Act of 2015. The White House is formulating a proposal to establish a “Mission Authorization” review.

Ben Roberts, the administration’s assistant director for Civil and Commercial Space, said the process would involve sending space proposals to “relevant agencies” for consideration of “compliance with international obligations, for being consistent with our national security and for protection of U.S. government assets in space” before going to the FAA for a launch license.

Sears warned that more U.S. regulation could “stifle innovation and really slow down the commercialization of space for U.S. companies,” while those of other nations proceed unfettered.

“I worry about a Mission Authorization agency review as being something potentially burdensome for a company like mine,” she said. “How do I know the approving agencies have our business best interests in mind? In fact, our interests might conflict with those of federal agencies. So where would I go for that unbiased authorization? If this is just implemented in the U.S., maybe I’ll go abroad to nations where the regulatory processes are more streamlined and more in tune with commercial practices.”

Dr. Josef Koller, a DoD senior advisor for space policy, agreed, adding that the U.S. controls 40 percent of all orbiting satellites today: “I feel like other nations are currently waiting and watching [to see what] the U.S. is doing in terms of space traffic management, rules of the road and standards.”

“We certainly believe that the current regulations that exist today, both domestic and international, from a treaty perspective, never envisioned a space environment like we have, and like we will continue to have in the future,” Sears said. “They’re absolutely insufficient to handle, not just the safety issue, but other issues as well, including enforcement.”

As a Nation, we can lead, but we need to lead after much dialog across multiple constituencies and with a plan that meets the objectives of our existing and emerging space entities, our regulators and our national security interests. I believe this can happen through increased commercial and civil cooperation first, with a level of transparency and best practices that guide us into the future of this exciting new space environment.