Satellite Is the Only Way to Transmit Tsunami Warning Data in Alaska

Intelsat General

The National Weather Service may use the least amount of bandwidth of any of Intelsat General’s customers, but someday, one of the tiny streams of Weather Service data going to the satellite could save lives. The data is collected from a string of approximately 10 remote sites along the coast of Alaska that measure minute changes in tide levels and incoming ocean currents to detect tsunamis. The sites, operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, are among hundreds around the United States that monitor tides and currents to help provide timely warnings to coastal residents in the event of an approaching tsunami.

The United States first established an official tsunami warning capability in 1949 in response to a tsunami that devastated Hilo, HI, generated by an earthquake more than 2,000 miles to the north in Alaska’s Aleutian Islands. The first U.S. warning center was set up in Hawaii. Subsequent earthquakes around the Pacific Rim in the following years, and the resulting destructive ocean waves on distant shores, resulted in gradual expansion of international warning capabilities and the opening of the National Tsunami Warning Center (NTWC) in Palmer, AK, about 45 miles northeast of Anchorage.

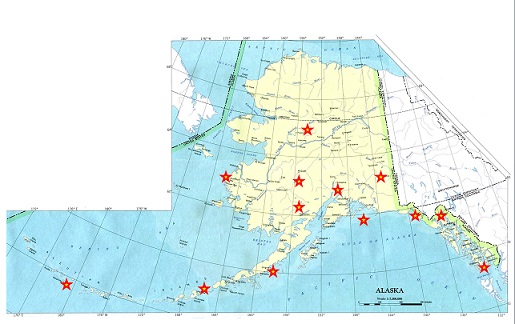

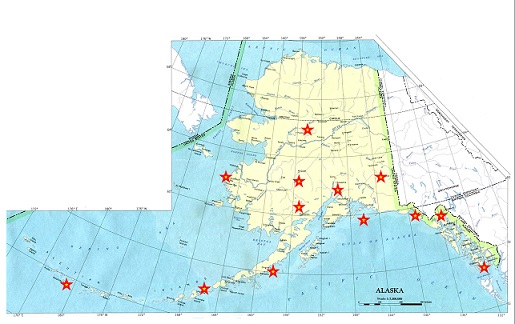

The Center in Palmer collects data from more than 400 tide sensors around the Atlantic, Pacific and Caribbean coasts of the United States and from 39 deep-ocean tsunami detectors. The Center also analyzes tidal data provided by the Canadian Hydrographic Survey and the Japanese Meteorological Agency. Readings from the these far-flung tidal sensors, coupled with earthquake data, enable experts at the Palmer facility to confirm the existence of the tsunami and its degree of severity in order to warn residents near the sensors in time to evacuate coastal areas. The sites served by Intelsat General are in remote areas of Alaska’s southern coast and more than a thousand miles out into the western reaches of the Aleutian Islands.

Intelsat General has provided the satellite capacity that collects the data from the remote Alaskan sites since 2004. All together, the sensors use the bandwidth in a continuous cycle of transmissions via VSAT dishes to one of the very few in-orbit satellites that has a unique beam reaching far to the north capable of serving Alaska and the Palmer facility.

Dave Reinke, Program Manager at Intelsat General who oversees the contract, said one of the challenges of providing the service is that the sites are so inaccessible. Any change on the satellite, (changing polarization, for example), would require a service visit to each site to adjust the VSAT dishes. One of the most remote tsunami warning sensors is on Amchitka Island, near the western end of the Aleutian chain on a beach at the bottom of a cliff.

Reinke said another challenge is the harsh Alaskan weather. One sensor is in a small village of 80 people, and the VSAT dish that sends sensor data to the satellite is on the roof a building. Sometimes the snow is so high on the roof that it blocks the line of sight between the dish and the satellite. The tidal sensors needs to be near a power source because solar panels for electricity are impractical, due to the cloudy weather much of the year and the presence of thousands of sea birds whose droppings would quickly cover the surface of a solar array.

“There is not a lot of satellite capacity in that part of the world and we’re glad we are able to provide the capability to support this needed service” Reinke said.