Military Support for Innovation Is a Matter of Culture

When Defense Sec. Ashton Carter reached out to Silicon Valley a year ago, the move was lauded as a Washington paean to innovation. Instead, it was only the first step toward a cultural-change goal.

“If we form a hypothesis and build an experiment, you have to be willing to be wrong,” said Gen. Paul Selva, Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, to the Center for Strategic and International Studies on August 5. “Then we can discount that idea and move on to another one. My experience with commercial industry tells me that innovation in commercial industry is exactly that process.”

He contrasted the commercial industry-like process the DoD is running with its Defense Innovation Unit Experimental (DIUx) outposts in Silicon Valley, Boston and, soon to open, Austin, Texas, with what he is dealing with now internally. The concept applies to commercial technology development all over the world, including the Washington, DC, metro area.

“Failure is not an option,” Selva said of ideas that come to him from the military. “Asking the hard questions is only acceptable if you know the answer, and none of that fosters innovation.”

It’s something industry learned long ago. “When I have finally decided that a result is worth getting, I go ahead on it and make trial after trial until it comes,” said Thomas Edison in an 1898 article in Success Magazine. This was after he acknowledged 3,000 trials before getting two answers he needed to invent the electric light.

An article in the September 4 issue of Financial Times (subscription only) acknowledged DoD’s history of support of Silicon Valley innovation. The concept of Siri, Apple’s voice-recognition technology, began with funding by DoD at Stanford Research Institute. The Global Positioning System was developed by the military for missile guidance before it was transitioned to companies that have used it to help convert mobile phones to smartphones.

But “Silicon Valley is a long way from its roots when it was funded by the DoD,” Steve Blank, an entrepreneur and professor at Stanford University, said in the Financial Times article.

So is innovation writ large. Technological advancements that will impact the services “are more likely going to come from innovation in the commercial sector than they will from real technological change inside our militaries,” Selva said.

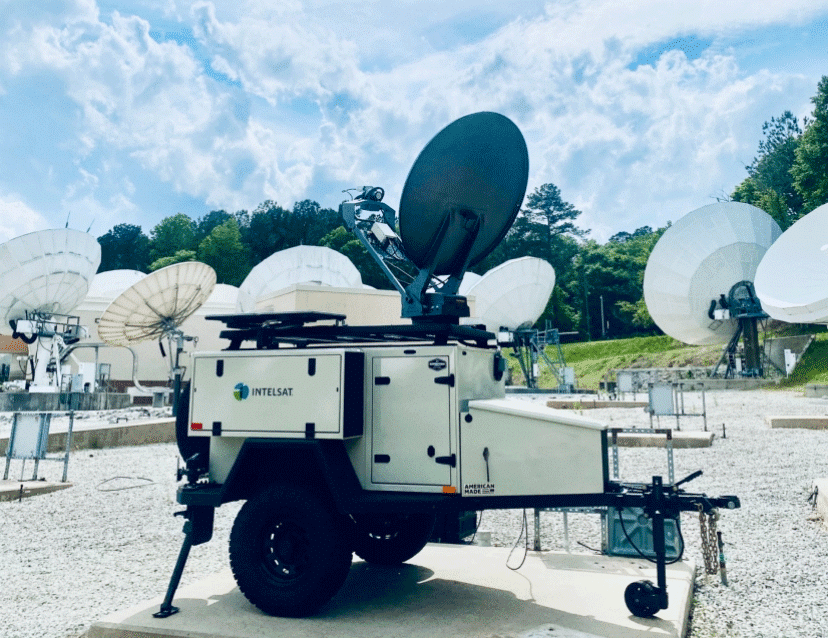

Illustrations of that reality abound. They include the Intelsat EpicNG constellation of high-throughput satellites, built on a three-year time line to send data faster than ever before. Technological advances are continuous, and each of the satellites in the EpicNG constellation launched over the coming years will be more advanced than the last.

The military is trying to change the development time limitation issue with a move back to prototyping, but success with such an effort will only come if the willingness to be wrong can be advanced by people like Selva and Carter.

“Our mantra is to move fast and break stuff,” said Josh Wolfe in the Financial Times article. He is a founder of Lux Capital, which invests in start-ups developing technology that has both military and commercial applications.

Among the reasons that defense needs industry is investment dollars. In the mid-1980s, the U.S. government accounted for 50 percent of global research funding, but today that amount is less than one-tenth of one percent, a figure the Financial Times quoted from a New York University report.

Still, said Carter in an April speech at Stanford, “our budget invests nearly $72 billion in R&D. Now, to give you a little context, that’s more than double what Apple, Intel and Google spent on R&D last year combined.” But he acknowledged that only $12.5 billion of that was DoD R&D dollars that went into labs and engineering centers.

Ironically, some of that is invested in the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), which uses it to contract industry and academia to prove – or disprove – programs that can result in military technology. It is the same process that has produced commercial success — yet no other DoD agency conducts programs in this fashion.

Industry is investing money in technology development that ultimately can benefit the military. It’s up to the government to take advantage of that investment in ways such as more and better use of commercial satellite communications, hosted payloads and ground services.

That is a cultural change the military doesn’t have to go to Silicon Valley, Boston or Austin to adopt.