Military SatCom Health Should Drive Decision Making, not Delay It

With growing concern about emerging or potential threats in space, the U.S. military is challenged to maintain and enhance capabilities to cope with an uncertain future. That challenge means delayed decision making about follow-ons for such programs as the Advanced Extremely High Frequency (AEHF) system and Wideband Global SatCom (WGS) which could be costly – and not just in dollars.

The military satcom constellation is “as healthy or healthier than at any time in history,” said Doug Loverro, assistant DoD secretary for space in a recent article in Aviation Week.

That good health is good news, but it is no basis for complacency in space. While officials ponder several options for the future, potential space adversaries are moving – innovating and launching vehicles that could become orbiting threats. Given the ponderous nature of funding and developing space technology for military use, decision-making delays feed a fear of the future. For a civilian government example, look no further than National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s delayed implementation of replacement satellites that endangers weather-forecasting during what is fast becoming the most ferocious and erratic period of storms in history.

The AEHF program is just one example of how long it can take to field a military satellite constellation. Nine years elapsed between letting the design contract in 2001 and launching the first satellite in 2010, and by the time the fourth platform is aloft, scheduled in 2017, the first satellite will be only seven years from its predicted demise, in 2024. Two more of the $1 billion satellites are planned, with launch dates to be determined.

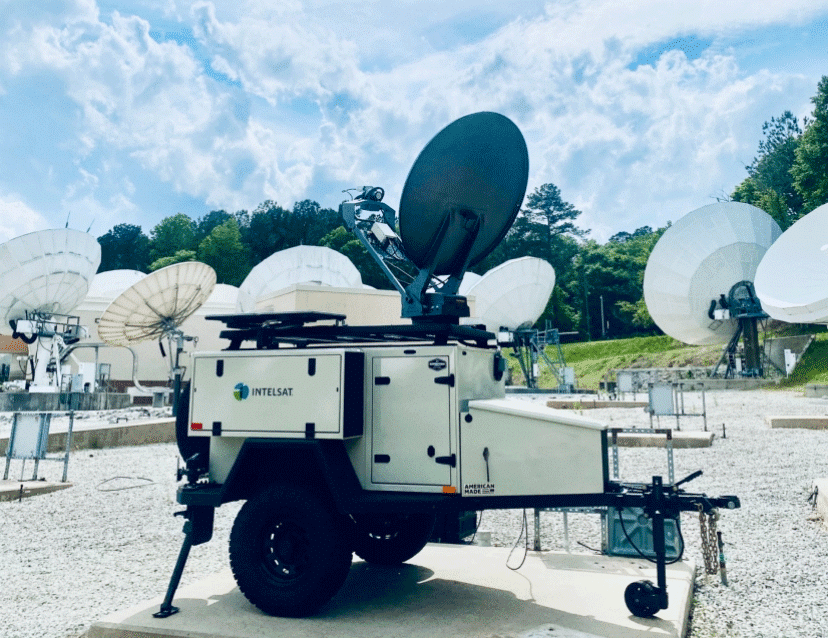

Many envision an Air Force-commercial industry partnership in space, with the military focusing on the most secure satellites – those with Presidential nuclear signal capabilities, such as the AEHF – and commercial operators taking on the brunt of the communications chores, along with WGS, both in space and on the ground.

The commercial communications segment includes OneWeb, an Intelsat partner, and its 648-satellite constellation, due to launch into low-Earth orbit in 2018.

“The defense department is reaching the same conclusions [as NASA] – obviously our needs are different – that by leveraging commercial entrepreneurial and coalition capabilities, we can then take our defense dollars and focus on those really high-end capabilities we need,” Loverro said in the Aviation Week article.

He added that by working more closely with the satellite industry, DoD could find new options for buying communications capacity and could also influence commercial satellite design and capabilities.

In this, Loverro acknowledged long-standing requests by industry and Congress for longer-term capacity leases that could drive down prices for the military, rather than one-year agreements that have too long been an inhibiting obstacle to rational planning. He also referred to industry’s often-expressed desire to be included at the front end of planning the DoD’s satellite architecture, so as to better integrate commercial and military capability from the beginning of the innovation process, rather than as an adjustment near the end.

For now, though, these are ideas and options, and the clock is ticking ever faster because of competition in space. Decisions need to be made. Because commercial timelines are shorter than those of the military, and commercial technology tends to be developed faster, industry needs to be included in making decisions about capabilities the DoD will need from commercial operators.

Such cooperation is the way to keep those military – and commercial – SATCOM constellations healthy.