How Developing Countries in Asia Are Leapfrogging Other Developed Nations in the Way They Access the Internet

By Melvyn Chen, Marketing

In the opening chapter of Steven Levy’s book, “In the Plex – How Google Thinks, Works, and Shapes Our Lives,” he writes about joining a team of Google associate product managers (APM), a select group pegged as the company’s future leaders, on a trip to a remote village in India. There was not a single PC in this village and it had just been connected to the power grid a few years back. During one interaction, a Google APM tried to explain what Google and the internet was in the simplest terms to a young villager. Then the villager held up a simple non-smartphone and indicated, “Is this what you mean?”

What struck me as I read this was the date of the trip which was July 2007. This was barely six months after I had the fortune of sitting entranced among the audience in Moscone Center, San Francisco, watching Steve Jobs on stage repeat the lines, “It’s an iPod. It’s a phone. It’s an Internet communications device.” That was, of course, history being made and the launch of the iPhone. Even back then, I knew that it would change everything. I just didn’t know how. Like chess grandmasters who think several moves ahead, folks at Google were already thinking about future untapped markets and how they would interact with the internet and therefore, the Google search engine.

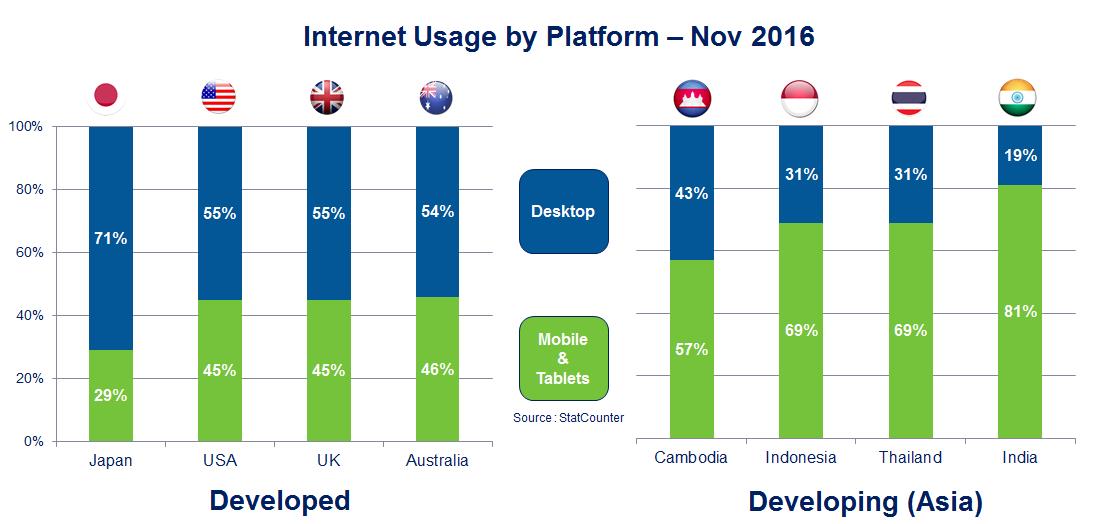

Google was certainly on the right track as 81 percent of internet usage in India today is on mobile devices versus traditional PC desktops. Other Asian countries like Thailand, Indonesia and Cambodia are also not far behind and I contrast this with other developed countries in the chart below. For many in developing rural regions, their first contact with the Internet or video entertainment will not be on a PC or television set but a mobile device. Hence, the internet giants have been focusing heavily towards planting their flag at this point of first contact as there is a general expectation that mobile will leapfrog PC as the primary screen – for consumers and ads alike. We see this with the Google search bar that is default on every Android mobile device and Facebook’s efforts with offering free limited internet access via internet.org.

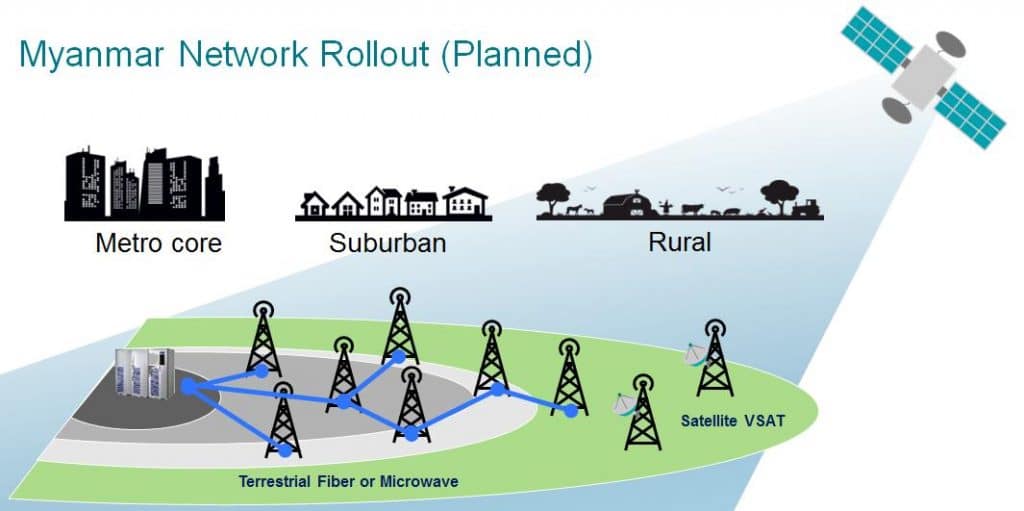

One reason for this leapfrogging behavior by developing countries in Asia is that with mobile networks, there is no need to lay fixed lines for last mile connectivity to the home or end user. For example, it is faster and cheaper to set up a single cell tower that can potentially connect multiple villages wirelessly. Coupled with the global urgency for governments to close the digital divide to alleviate social and economic inequality for rural regions, mobile wireless networks remain the infrastructure of choice to connect the unconnected. However, while there is no need to physically connect to the home or end user, the cell towers still need to be connected back to the main telco hub that can be hundreds of miles away. Connecting the towers via terrestrial infrastructure like fiber or microwave may not always be feasible due to cost or geography so a flexible and easily scalable alternative like satellite is used.

A good example of how satellite was used to augment the rollout of mobile networks is in Myanmar. Myanmar was one of the last major telecoms greenfields on the planet before the telecoms market opened up in 2013. This Southeast Asian nation of 51 million, formerly known as Burma, had fewer than 2 million Internet users. But in 2013, the new democratically elected government put in place a number of telecommunication reforms as part of its effort to open the country to global markets. In the three years since, internet use in Myanmar has soared to around 39 million internet users, driven mainly by mobile phone use.

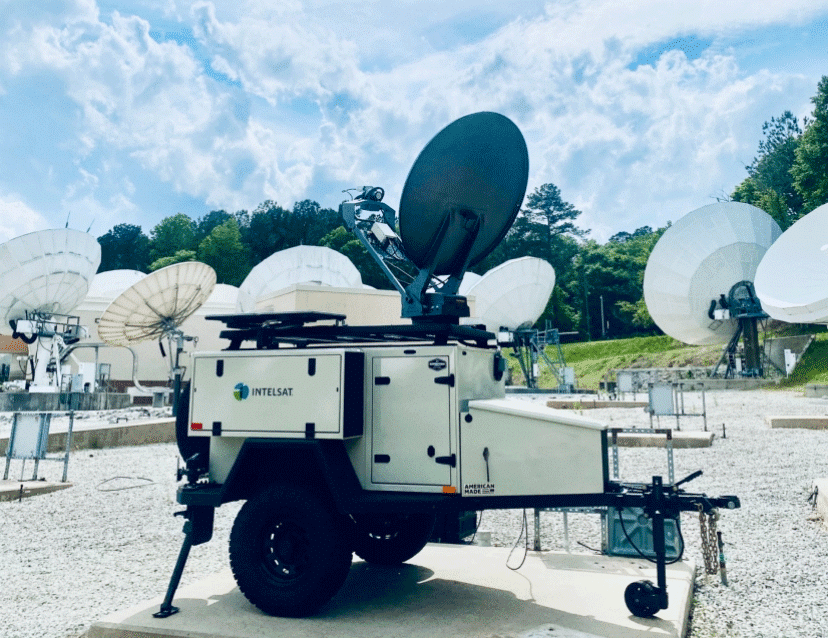

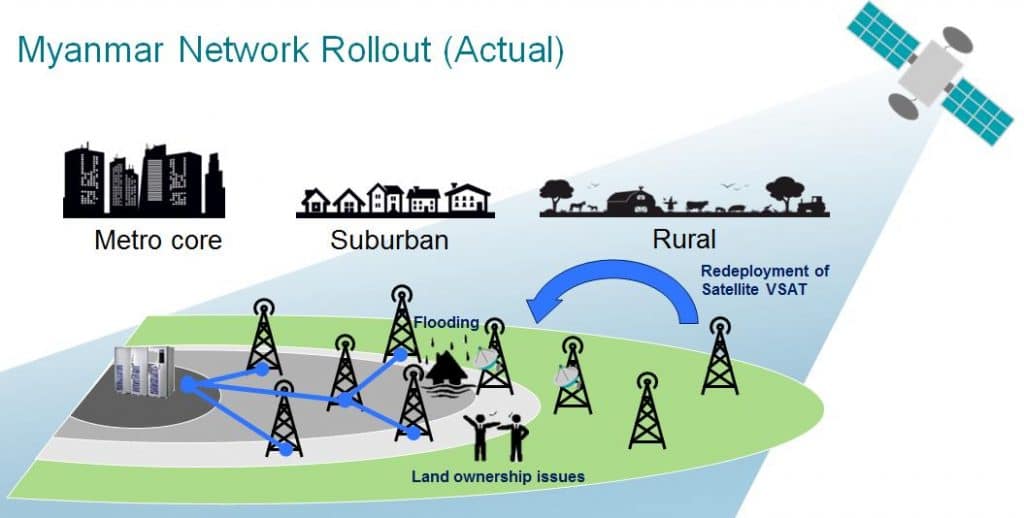

Once the market opened up, mobile network operators needed to roll out their mobile network as quickly as possible to capture the first mover advantage. However, the network rollout was not without its challenges. Thousands of towers needed to be built, thousands of miles of fiber needed to be laid and the mountainous terrain in parts of the country posed a formidable obstacle. One mobile network operator planned to use terrestrial infrastructure to connect the metropolitan and suburban areas while contracting with Intelsat and our local service provider partner to connect certain rural areas via satellite.

However, during the actual execution, the terrestrial infrastructure rollout ran into snags like flooding which is common during the rainy seasons as well as land ownership issues and was delayed. The decision was then made to redeploy the satellite VSATs (Very Small Aperture Terminals) from the originally planned rural sites to the edge of the current terrestrial network rollout. The satellite VSATs were then moved further out again in a stepwise fashion once the terrestrial network rollout caught up. This was made possible by the flexibility of satellite as terrestrial infrastructure like fiber and microwave cannot be re-deployed as quickly and easily.

Another unforeseen variable in Myanmar was the amount of data consumption. When the telecoms market opened up, most analysts believed that there would predominantly be just voice/SMS traffic and very little data traffic for the first several years. However, the rapid decrease in the price of 3G/4G smartphones as well as a hunger of the Internet triggered an explosion in data usage. In Nov 2015, just two years after the telecoms market opened up, Ooredoo Myanmar reported that 80% of the phones on their network were smartphones and that their average data consumption was over 650 megabytes per month on average. To put that into perspective, in 2011, the average data usage of a customer on the 3 network in UK was 450 megabytes per month.

One phenomenon I’ve observed in my visits to Myanmar is the prominence of Facebook. If you buy a smartphone today in Myanmar, Facebook is almost always pre-installed by the shop. In fact, the shop staff would even set up a fake account for the buyer. The reason why it’s fake is because most people in Myanmar use Facebook not as a tool to look up their high school sweetheart but as a news portal. In fact, the Internet and Facebook are one and the same for many people in Myanmar. One of the mobile network operators even remarked to me that Facebook accounted for one third of his overall network data traffic.

This unforeseen increase in data traffic definitely had an impact on the mobile network. The initial assumptions used for dimensioning the network were completely off the mark. As satellite is easily scalable, Intelsat was able to quickly provide more bandwidth, almost as easy as flipping a switch, to our mobile network operator customers to meet their increased data requirements. The process would have been nowhere as easy if it was the terrestrial infrastructure that was under-dimensioned. Imagine having to upgrade the microwave hardware at every single tower!

Today, Intelsat is doing its part to bridge the digital divide by currently providing satellite capacity to all the mobile network operators in Myanmar to assist in their network rollout. In addition, we have also signed a significant lease agreement with the Ministry of Trade and Communications in Myanmar for their domestic government connectivity requirements. Furthermore in Q1 2017, IS-33e, our next generation Epic High-Throughput Satellite, will come into service over Asia and will bring along benefits like lower cost per bit and reduced ground hardware requirements. Thus, we expect to continue to play a major role in providing connectivity to the region.