Charyk Helped Chart the Course of Satellite Communications

Skeptics abounded in 1963 when Joseph Charyk went looking for investors and customers for the new, quasi-private Communications Satellite Corp. (COMSAT). The company came into being when President Kennedy signed legislation designating COMSAT to represent the United States in the nascent international satellite realm.

With Sputnik having launched just six years earlier, satellite technology was in its infancy. U.S. military and communications industry leaders thought low- or medium earth-orbit constellations could meet their needs. But Charyk advocated placing a few platforms in geosynchronous orbit that could relay signals over wider areas and provide global service.

In August of 1964, with Charyk as its founding president, COMSAT helped create, and was the majority owner of, the International Telecommunications Satellite Consortium, known as Intelsat. Eight months later, Intelsat launched its first satellite, Intelsat I, colloquially known as Early Bird. This first satellite communications platform relaying signals from 22,300 miles up verified Charyk’s belief in geosynchronous orbit for SATCOM.

Designers and engineers made many leaps in technology over a half century to get from Intelsat I, with either 240 voice circuits or one TV circuit — Early Bird could not do both at the same time — to today’s Intelsat fleet of more than 50 satellites. The advances from Early Bird’s capability to that of today’s growing Intelsat EpicNG high-throughput satellite constellation took more than a few innovators and dreamers.

Charyk, who died in Delray Beach, Fla., on September 28 at age 96, was one of those dreamers.

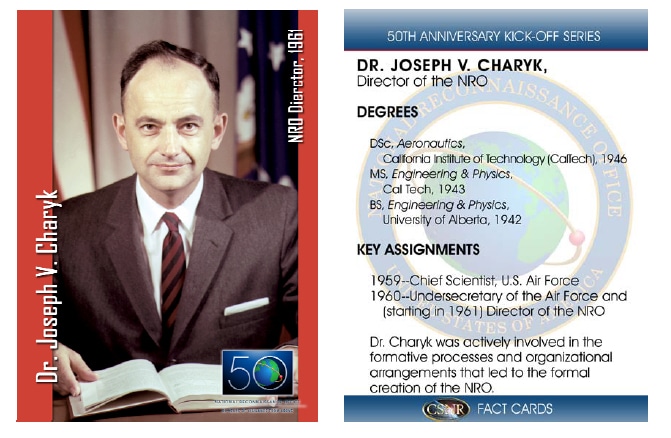

Born in 1920 to Ukranian immigrant parents in Alberta, Canada, Charyk moved to the United States to earn a doctorate at CalTech. After teaching at Princeton, then heading Ford Motor Company’s non-automotive business, Charyk was named the Air Force’s chief scientist, then held other government positions that included being the first head of the National Reconnaissance Office – all while trying to get back to industry. Upon being named to head COMSAT, he worked to raise capital and customers for a company still seeking an identity.

His chief problem involved beliefs that geostationary satellites would be too heavy to be launched with the propulsion means of the day; that they were limited to a lifespan of about 18 months; and that a half-second delay in transmitting voice communications would be unacceptable to users.

Intelsat I weighed 76 pounds and was in service for four years. That it got to space at all was a saga. In an oral history of COMSAT in 1985, Charyk recalled an early meeting with Gen. David Sarnoff, head of RCA. Charyk believed RCA would be an ideal customer and investor, and so made his pitch for support.

Sarnoff replied, “Well, you’re talking about doing things that may or may not work, that may or not make economic sense.” RCA had invested heavily in equipment for high frequency radio stations.

Said Charyk: “Regardless of how it evolves, satellite communications are going to be the way of the future, and your high frequency radio stations are going to become obsolete.”

Charyk recalled that Sarnoff’s staff chimed in objections, then stopped when Sarnoff raised his hand and said, “You know, I think he’s right.”

Sarnoff became a customer and on Oct. 26, 1965, six months after the first satellite’s launch, RCA broadcast the “Town Meeting of the World” on CBS, with students from London, Belgrade, Paris and Mexico City talking via Intelsat I with former President Dwight D. Eisenhower, UN Ambassador Arthur Goldberg and then-Solicitor General Thurgood Marshall. It was the first two-way commercial television program transmitted by satellite and the first time multiple points on both sides of the Atlantic were linked by television.

The trip from there to today was charted by Charyk, who ran COMSAT for 22 years until his retirement in 1985, and others who pioneered satellite communications.

“The thing that impresses me about the old stuff is that what used to be a remarkable thing is just accepted as routine,” Charyk said in a Washington Post story in 1981. “.. The idea that I can see an event or talk to anyone in the world is now accepted as a routine thing.”